The story of two transformations that I shared last week have driven a lot of my thoughts about how Change Catalysts can support organizations through transformation, specifically around the topic of loss.

Knowing that loss is always present in change is a start. It’s also critical to know that loss presents in many ways.

And that not always clear that loss is what we’re experiencing.

No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear

~ C.S. Lewis

Coping with this loss isn’t easy, but there are patterns and anti-patterns which can help. I’ve listed a few that I’ve used here in multiple settings and found to be effective.

Patterns

Honor the Loss

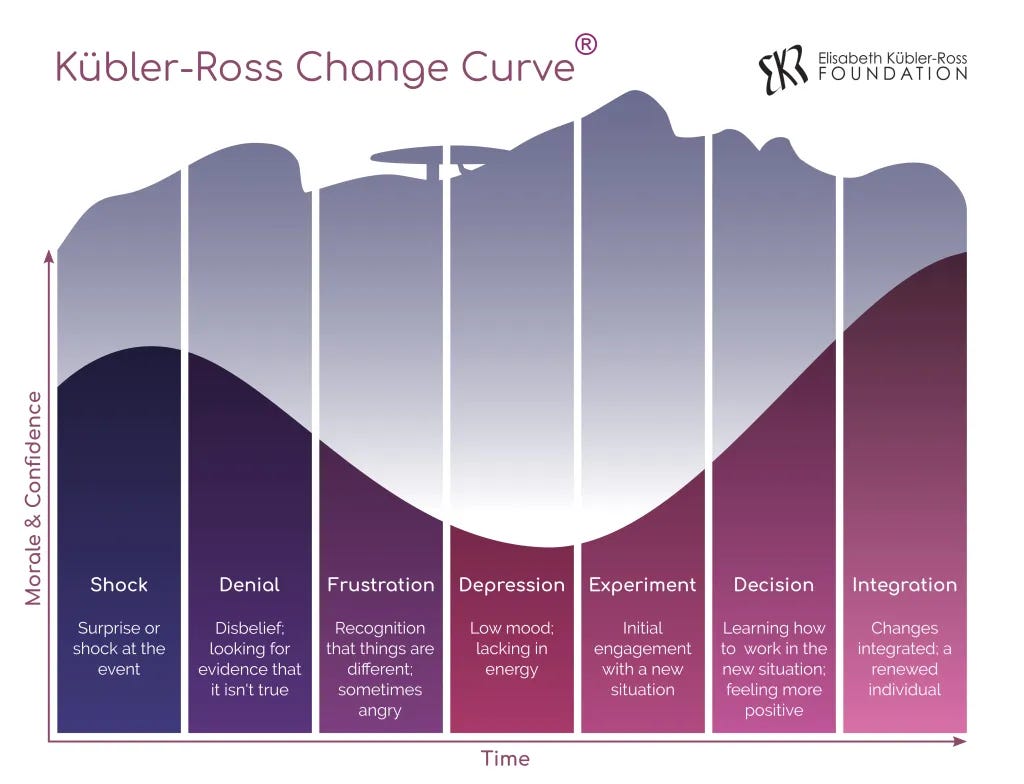

The Kübler-Ross Change Curve is a good place to start. Based on her work in On Death and Dying, the curve describes people’s responses to change, and specifically how we cope with loss.

One exercise that I’ve seen used successfully is to have folks plot where they, and others, are on the curve, and talk about why. Take them through an exercise to consider what the organization can do to move forward.

Uncover continuity

While some things lost, parts remain.

5 Whys - at its core this technique is about getting to the quintessence of the issue at hand. Here the root that we’re looking for are the critical and important pieces of the culture that should remain, even as other things change.

I’ve extracted a template I’ve used and added a (fictional) example of how it can be used to understand what remains when something important is lost.

Enlist and empower change catalysts

At iZotope our Change Catalyst team was a dozen (more than 20% of the company) people, representing every function in product development. We spent nearly 3 months learning the theory and debate the practices of SAFe before deciding which to keep, which to modify, and which to throw out.

I drew heavily from Kotter’s Guiding Coalition for this work, and I highly recommend it.

Good enough for now, Safe Enough to Try

We used this heuristic from sociocracy without even knowing it existed. Quarterly planning was implemented straight from the SAFe 3.0 playbook as PI planning. 2 days, every team, one room, briefings from execs with all the relevant context. But we had concerns about the amount of time and effort spent on the approach.

So we were transparent that this was an experiment; we might have to radically alter it, and we sought out feedback before, during, and after the event.

As a result we threw out one of the main elements of PI Planning - business value (BV) scoring. The feedback we got was scathing - these are actual quotes

“The whole company business value thing was a disaster”

“Assigning business value publicly…makes it feel like a sentencing”

“… you are not going to go up against (exec) in front of the whole company. Even if they are super wrong....super super super super uninformed and wrong.”

As a result, we dropped BV scoring entirely, and appologized to the company as an executive team. That willingness to adapt based on experience bolstered peoples’ willingness to experiment, and lessened the anxiety about loss.

Anti-Patterns

Toxic positivity - Dismissing the concerns

Accentuating the positive, and ignoring the negative can feel to a leader like the best way to keep morale up. They want to give that St Crispin’s Day speech that rouses everone to fight against impossible odds - that’s LEADERSHIP! But the VP of ___ is not Shakespeare, and the CXO is not Henry V. And this is not a play - it’s real life.

The intention is good - by not stop talking about what could go wrong, what we might lose, we focus only on what we’ll gain! But the impact is the exact opposite - by minimizing and dismisssing concerns about loss, leaders make them seem more likely. What’s going through your teams’ heads?

If the CXO isn’t thinking about it, well then we must all the more! It’s clear that they just don’t get it, and need our help to understand.

Silo’d / Solo Design

Shielding one’s teams from uncertainty, fear, and loss is a nobel impulse, and often contributes to the decision to “have the answers” on a transformation before involving the team.

But outsourcing the design to a management consulting company didn’t increase confidence, or lower anxiety. It did the opposite.

No outside firm can truly lead change management for an organization. And it is only through that process that loss can be integrated, and change can be accepted.

In this case the very design document was not distributed; only redacted copies, which lacked a lot of the context on why things were going to change the way they did.

Implementation without Feedback and Iteration

Part of the package from the management consulting company was a playbook for implementation.

This many coaches for this many teams.

This training for role x, and that training for role y

New processes 1, 2, and 3 have templates I, II and III

The support of scores of contractors let the technology group run through the playbook in about 90 days. And after that point, support dropped dramatically.

What most people didn’t know was the compromises that were made - for efficiency, cost, and other reasons. Large swaths of the playbook were not implemented. Even if you didn’t know there were pieces missing, you felt them.

For example, the plan had clear alignment of teams to executives - meaning every team would know which executive they could go to for context and support.

That mapping wasn’t implemented as designed, leaving multiple execs with influence over the same teams, and some with no implied influence at all.

Because of this, execs had to use informal channels to get work done, in opposition to the notions of transparency and alignment that teams had learned in the training.

Even worse, there was zero appetite for iterating on the system, even where there were obvious, and serious problems. Leadership and the budget (8 figures) were exhausted by all the change. Stakeholders were anxious to see the return on their investment.

Gaslighting

Perhaps too harsh? Maybe the right phrase is “optimism bias,” or “cognitive overload.” Driven largely by pressure to perform, and fear of being blamed for a multi-million dollar slowdown and failure, problems were minimized, or explained away as growing pains. Systemic problems were sometimes recast as local ones, and managers were directed to “solve the problem” themselves.

Meanwhile there were two highlights for leadership at the time

Focus on the numbers - teams transformed, Product Owners hired, people put through training. Things that slowed down that progress were actively managed away.

A misuse of “adopt the principle, adapt the practice.” A great heuristic, in some places it was used to just “get through” aspects of the transformation, and the difficult work of really adopting the principles was left for later. Or dropped entirely.

It wasnt’ all bad

In fact even many years later in the midst of yet another transformation several product directors came up to me and said they were worried that we’d lose the gains made in this transformation, that we were “giving up on agile.”

So this was a flawed transformation, but not necessarily a failed one. And to be fair, every transformation has its flaws.

Now What?

Are there any lessons, any takeaways from these stories for us, aside from “follow the patterns, and avoid the anti-patterns?” For sure - especially related to managing and supporting people through loss. Here are my top 4

Cherish your Change Catalyst coalition

This team is the foundation of your whole transformation. You want them engaged before you start, while you implement, and even after you’re “done.” Because change never stops - it only varies in intensity.

For supporting change and loss, nothing beats having a friend in the hole with you. And a committed Change Catalyst team is just that. There are folks from that initial transformation among my most trusted advisors, some of whom helped me with these articles.

However hard you think it is - it’s harder than you think

Loss and change come out in unexpected ways. What seems like a simple adjustment to a process can deeply impact someone’s sense of self-worth. The hard thing isn’t figuring out the new process - it’s separating out the change in process from the loss that person is experiencing.

Stay focused but be willing to flex

We are used to the idea that methods can change, but outcomes and vision should remain constant. Not so with transformation. The work is the very definition of emergent.

The vision and the outcomes, even if co-created with the teams at the start, may not be what you truly want to accomplish. Point your compass towards your values, and be willing to flex everything else.

Remember that this work is a privilege, and stay grateful

Transformation is the most difficult work I’ve ever done, and it is by far the most rewarding. It is a true previledge to support organizations through transformaiton, and people through loss. I’ve grown and learned more work in this area than from any other I’ve done.

That gratitude provided the grit needed to hold space through some of the most challenigng professional experiences of my life. And I’m grateful to the organzations, leaders, teams, and people who allowed me to do this work.

Thank you all, very much.